Reproduction

As this species is new to science, nothing is currently known about its reproductive biology or life history strategies and I have therefore relied on knowledge of similar species within the Eysia genus, and of opisthobranchs more generally, to infer the likely methods of reproduction in Elysia sp.

Opisthobranch sea slugs are simultaneous hermaphrodites that have evolved complex reproductive systems to facilitate internal cross-fertilisation [4-6]. In some species, resorption of donated sperm (allosperm) from another individual has been demonstrated, and it is thought that this process is probably fairly widespread throughout the opisthobranchia as the presence of a gametolytic gland is common for most groups [5,7,8]. Opisthobranchs donate and receive sperm in a head-to-tail position, and standard copulatory behaviour involves mutual insertion of the penes of both partners [5,9,10]. Although there is a common theme, mating in the opisthobranchs is highly varied, with some species, especially the sea hares, known to form mating chains [5,9,12,15], while others are known to alternate sex roles during copulation [11], or transfer sperm by externally attached spermatophores [5].

In simultaneous hermaphrodites such as Elysia sp. it is thought that the reproductive success of the female aspect of the slug may be limited by how readily available nutrients for egg production are, and not by the availabilty of allosperm [16]. This can lead to conflicts of interest over how the donated sperm is used, as in many cases it is digested via the gametolytic gland rather than used for fertilisation [17]. Further conflict is created if an individual mates repeatedly as a female before fertilisation occurs, leading to sperm competition [18-22]. Some species have taken this even further and practice conditional reciprocity [10]. This has been demonstrated for both Elysia timida and E. patina [10,15], and will be discussed below.

Hypodermic insemination, whereby sperm is injected into the partner's

body surface, is also widespread in the sacoglossans [10,12-15]. Some species mate solely via hypodermic insemination, and many have developed highly specialised penial armature or stylets, though it is not necessarily characteristic as many species that mate via hypodermic insemination lack this armature [10,13-15,22,25]. Some species that practice hypodermic insemination inject sperm directly into receptive bursa, whilst in other species it can be injected anywhere in the body and presumably has some ability to navigate to the reproductive bursa. [10,13-15,21,22,23]. Species mating via this method mostly inject sperm into gametolytic vessels near the pericardial veins, leading some to theorise that the sperm may travel through these veins to reach the female reproductive system [15].

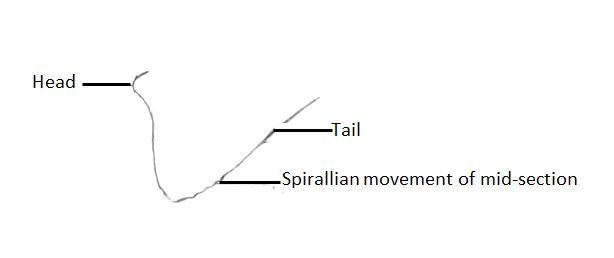

Sperm morphology has been described for E. timida, and is similar to that described for E. patina- distinctly thread-like in shape, lacking a prominent head, and with vigorous spirallian movement of the middle section as seen in Figure 2 [7,12]. It has been noted that although E. timida practices hypodermic insemination, no penial armature has been detected in the species [7]. This is not unsurprising, as although the presence of a penial stylet is widespread throughout the sacoglossa, it has thus far been found to be absent in all species of Elysia with the exception of E. patina [7,12]. Alternative methods of hypodermic insemination without the use of a penial stylet likely include turgor pressure or enzymatic attack, though neither have been investigated within the Elysiids [7,23]. Diagrams of the reproductive anatomy of two species of Elysia, E. patina and E. timida, are available on the Internal Anatomy page of this site, and demonstrate the high degree of variability of reproductive anatomy within the Elysia genus.

Mating in Elysia timida

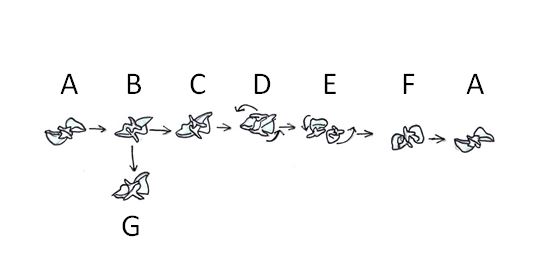

The mating behaviour of E. timida has been well studied, and is incredibly unique in that both hypodermic insemination and insemination into the female aperture are involved [10]. In E. timida the copulation process begins when two individuals meet head-to-head with rhinophores and heads seen to touch, then turn their heads to the left and begin to move down the right hand side of the other individual such that they end up positioned head-to-tail: the customary copulatory position seen in most sacoglossans, steps A and B in Figure 1 below [10]. Copulation in E. timida is two-fold, beginning with a round of hypodermic insemination whereby both partners extend their penes to reach the dorsal surface of the other where the main insemination site was found to be the dorsal notum, the posterior aspect of the pericardium, steps C-F in Figure 1 [10]. In between each hypodermic transfer attempt both individuals partially retract their penes and begin to circle anti-clockwise in a highly synchronised manner [10]. Several hypodermic transfers are seen in each copulation sequence [10]. Following the final hypodermic transfer and stereotypic circling movement, individuals returned to the copulation position (head-to-tail) once more, but this time mutually inserted their penes into the female aperture of their partner with sperm transfer occurring near to simultaneously, steps A, B and G in Figure 1 [10].

It has been demonstrated that E. timida display a clear preference for reciprocal sperm transfer [10].

Mating pairs have been observed to display atypical mating behaviours when only one partner transfers sperm hypodermically, and in these cases hypodermic insemination is not followed by insemination directly into the female aperture as would be expected, suggesting that not only do these slugs have a preference for reciprocal sperm transfer, they also have a control mechanism in place to ensure it [10]. There are also observations that suggest conditional reciprocity in the final mating phase, with some individuals having been observed touching the female aperture with their penis several times before final insemination as if waiting for the partner to act reciprocally [10]. In pairs where only one individual transfers sperm in the final mating phase, an extensive circling phase is seen, during which time the individual who had transferred sperm repeatedly protrudes and retracts its penis, indicating that this might be a conflict over failed reciprocity [10]. It has been anecdotally noted that there appears to be a high degree of synchrony within pairs, but variable to little synchrony between pairs, raising the possibility that partners may adapt their behaviour to suit that of their mate, clearly demonstrating the plasticity of mating behaviours in E. timida [10].

Figure 1- The mating process in Elysia timida. A: Initial head-to-meeting, B: Individuals moving into copulatory copulation, C: Hypodermic transfer, D & E: Stereotypic counter-clockwise circling, F: End of circling behaviour and return to head-to-head position (A), G: Sperm transfer directly into female aperture. Note that in species which do not practice hypodermic insemination, reproduction would move from A through , and lastly G. Diagram adapted from Schmitt et al, 2007 [10].

Figure 2- Single spermatozoa of Elysia patina. Note that E. patina sperm move in a sinusoidal manner congruent with the sperm morphology. Adapted from compound microscope images in Jensen, 1986 [15].

Figure 3- The copulatory position seen in Elysia subornata (left), a hypodermic inseminator, differs from the standard head-to-tail copulation position seen in most Elysia species (right), demonstrating the high degree of variability in reproductive strategies throughout the genus. Adapted from Jensen, 1986 [15].

|